On 17 July 1984, a redundant Class 46

"Peak" locomotive was deliberately crashed into a nuclear

flask wagon on BR’s Old Dalby test track. Although the ant-nuclear

lobby dismissed the demonstration as a high profile publicity stunt

conducted under staged conditions, the steel-lined nuclear flask survived

the 90mph impact unscathed. The general public, it seemed, could rest

assured; in the event of a major accident, there would be no release

of hazardous radioactive material. In fact, spent nuclear fuel has been

transported by rail since the early 1960s and, in over forty years,

there has never been a significant incident. For the last decade, such

traffic has been handled by Direct Rail Services (DRS) which, until

recently, was a wholly owned subsidiary of British Nuclear Fuels Limited

(BNFL), the public sector company that manages the Sellafield nuclear

plant in West Cumbria. BNFL’s move to create its own rail division

was essentially a strategic one to ensure the continued transportation

of nuclear waste by rail after privatisation.

DRS was formally established in February 1995 and commenced

operations out of Sellafield the following October, when a pair of ex-BR

Class 20s made the short journey down the Cumbrian Coast to collect

a consignment of imported nuclear waste from Barrow Ramsden Docks.

Of course, nuclear power in general, and nuclear waste

in particular, remain highly contentious issues. A typical uranium fuel

rod will last for about four years before the build up of fission (waste)

products makes it less efficient. Once removed from the reactor core

and allowed to cool, the spent fuel rods are loaded into specially designed

nuclear shipping flasks and rail-hauled to Sellafield for reprocessing.

Half of the UK’s nuclear power stations can boast

direct rail links, whereas the others are served by "remote"

rail heads such as Bridgewater (for Hinkley Point) and Valley (for Wylfa).

The flasks are first moved to one of three key "hubs" –

Willesden (for Dungeness and Sizewell), Crewe (for Hinkley Point, Oldbury

and Wylfa) and Carlisle (for Hunterston, Torness and Seaton-on-Tees)

– where they are marshalled together to form a "block"

working for Sellafield.

In the aftermath of 11 September 2001 and the increased

terrorist threat, some sections of the media highlighted the fact that

details of nuclear train movements were readily available in the public

domain via Freightmaster. In fact, the timings listed in Freightmaster

are largely based on private observations; for operational and security

reasons, diagrams vary from day to day and many trains run only "as

required".

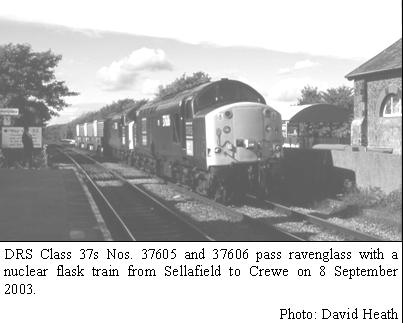

Virtually all nuclear flask workings are double-headed,

primarily to ensure against a single locomotive failure which could

leave a train stranded either in the middle of nowhere, or in a busy

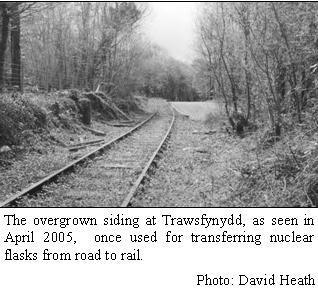

urban area. As most power station loading points are little more than

basic sidings (often with no run round facilities), double-heading or

"top and tailing" also provides greater operational flexibility.

On arrival at Sellafield, the flasks are unloaded and

the spent fuel rods moved to the reprocessing plant where they are dissolved

in hot nitric acid. This separates out the re-usable uranium (96%) and

plutonium (1%) from the waste products (3%); the uranium can then be

turned back into pellets for new fuel rods and the plutonium combined

with uranium to form a new Mixed Oxide Fuel (MOX). The highly radioactive

waste is vitrified and stored.

As previously noted, Sellafield also receives nuclear

waste from Europe and Japan via BNFL’s own import terminal at

Barrow. The trip workings from there to Sellafield are rarely photographed

which is a shame, because they offer enthusiasts the only opportunity

to view "raw" nuclear flasks on the move; all flasks from

domestic power stations have a large box-like ventilation hood placed

over them before their journey begins, leading many observers to incorrectly

assume that this is the flask itself.

There are also occasional movements from the Royal Navy dockyards at

Devonport and Rosyth of spent fuel rods from nuclear submarines. Unlike

the civil power station traffic that uses the standard FNA nuclear flask

wagons, the MoD employs two huge transporter trucks rather like transformer

wagons to carry the waste. These trains are classified under the Official

Secrets Act and always travel to Sellafield with at least one support

coach containing an armed escort

.

Amongst the other hazardous cargoes moved to Sellafield by DRS are bulk

chemicals used in the nuclear recycling process, namely nitric acid

(from Sandbach) and caustic soda (from Runcorn Folly Lane). There is

also a local trip working of low level nuclear waste from Sellafield

to British Nuclear Group’s Drigg repository. Following a major

restructuring of the UK’s nuclear industry, the Sellafield site

is now owned by the Nuclear Decommissioning Authority (see below), although

day to day operations are actually contracted back to British Nuclear

Group, a newly created subsidiary of BNFL.

In July 1999, DRS moved its headquarters from Sellafield

to the former BR Traction Maintenance Depot at Carlisle Kingmoor. Refurbished

at a cost of £1m, Kingmoor has provided the Company with a highly

strategic base alongside the West Coast Main Line from which to expand

beyond its core nuclear business. This process had actually begun a

couple of years earlier when DRS ran trials for both Tankfreight (a

logistics company interested in using rail to transport milk from Cumbrian

dairies to London) and Carlisle-based road haulier, Eddie Stobart. The

latter trial was supposed to have been conducted in secret, but as with

many of these things, word soon leaked out and a furious Stobart launched

a scathing attack on the railfreight industry, vowing never to use rail

again.

In early 2001, however, DRS won a contract with Scottish

logistics company, WH Malcolm, for a new Daventry-Grangemouth service.

This operation has grown from two trains a week to two a day including

a Daventry-Coatbridge flow and an Aberdeen service.

Additional business won during 2005 included a daily

Widnes-Purfleet Thames Terminal intermodal service for AHC (Warehousing)

Ltd., and a Network Rail weed-killing contract.

Considering its reputation as a niche operator, DRS

can boast a particularly interesting and varied motive power fleet,

which includes Classes 20, 33, 37 and 47. During its formative years,

the Company pursued a policy of buying (and then refurbishing) second-hand

locomotives from a variety of sources, but in January 2003, it signed

a deal with Porterbrook Leasing for ten new General Motors-built Class

66/4s. The first five machines, resplendent in a vibrant new DRS colour

scheme, arrived in the UK the following October and were immediately

put into service on the WH Malcolm traffic. This allowed the six ex-Hunslet

Barclay Class 20/9s (three of which worked to the Balkans in 1999 on

the Kosovo "Train for Life") to be withdrawn. Up until that

point, DRS had 21 Class 20s (including a number of ex-RFS Industries

examples used on the Channel Tunnel construction project) on its active

list, with a similar number in store pending possible refurbishment.

Many of these were in a particularly poor condition and in early 2005,

a small batch were sold to Harry Needle in exchange for several Class

37s. And, just as this article was in preparation, DRS announced that

it had sold its four Class 33s (always regarded as something of a specialist

fleet with no long term future) to Carnforth-based West Coast Railway

Company, again in exchange for two Class 37s. DRS has long favoured

this locomotive type and includes amongst its active fleet, nine of

the ex-BR European Passenger Services Class 37/6s. These machines were

heavily re-engineered during the early 1990s for use on Channel Tunnel

sleeper traffic but when the infamous Nightstar project was abandoned

in 1997, six of the twelve locos were put up for sale, and the fledgling

DRS quickly snapped them up. A further three were acquired from Eurostar

(UK) several years later. During 2004/05, DRS trialled several Class 87 electric

locos with a view to introducing them on the Malcolm logistics

traffic. This was in direct response to an SRA strategy document

which sought to eliminate diesel traction from the two-track West

Coast Main Line north of Crewe after full introduction of the

125mph Virgin Pendolino service. Whilst the 87s offered improved

acceleration and better performance (particularly on the tortuous

route north of Preston), DRS ultimately decided that the locos

did not meet the Company’s operational requirements, largely

because the facilities at Grangemouth and Daventry (and Kingmoor

depot itself!) are not electrified.

|

|

On 1 April 2005, ownership

of DRS together with many of the UK’s ageing nuclear assets

was transferred to the new Nuclear Decommissioning Authority (NDA).

As its name suggests, the NDA will oversee the decommissioning

and clean up of the UK’s nuclear legacy. There are now only

four first generation Magnox power stations still in operation:

Dungeness A, Sizewell A, Oldbury and Wylfa. The first two are

scheduled to cease operations in 2006, Oldbury in 2008 and Wylfa

(on Anglesey) in 2010. The Magnox reprocessing plant at Sellafield

is due to close by 2012. That does not, however, mean the end

of nuclear waste trains in the UK as there will still be flask

traffic (although much less of it) from the second generation

Advanced Gas Cooled Reactors, which should continue operating

into the 2020s. And during 2006, the Government will finally make

a decision on the country’s long term energy needs. With

the UK's oil and gas reserves rapidly depleting, an urgent need

to reduce harmful CO2 emissions, and renewable energy still in

its infancy, the tide is once again turning in favour of nuclear

power. We should not really be surprised. Despite its relatively

high capital costs, nuclear energy is extremely cheap; in fact,

one 6gm pellet of MOX fuel can provide the same amount of energy

as one tonne of coal.

DRS continues to follow the debate with interest

but the Company is now so firmly established in the railfreight

market that its long term future seems assured, regardless of

UK energy policy.

Virtually all nuclear flask workings are double-headed,

primarily to ensure against a single locomotive failure which could

leave a train stranded either in the middle of nowhere, or in a busy

urban area. As most power station loading points are little more than

basic sidings (often with no run round facilities), double-heading or

"top and tailing" also provides greater operational flexibility.

On arrival at Sellafield, the flasks are unloaded and

the spent fuel rods moved to the reprocessing plant where they are dissolved

in hot nitric acid. This separates out the re-usable uranium (96%) and

plutonium (1%) from the waste products (3%); the uranium can then be

turned back into pellets for new fuel rods and the plutonium combined

with uranium to form a new Mixed Oxide Fuel (MOX). The highly radioactive

waste is vitrified and stored.

As previously noted, Sellafield also receives nuclear

waste from Europe and Japan via BNFL’s own import terminal at

Barrow. The trip workings from there to Sellafield are rarely photographed

which is a shame, because they offer enthusiasts the only opportunity

to view "raw" nuclear flasks on the move; all flasks from

domestic power stations have a large box-like ventilation hood placed

over them before their journey begins, leading many observers to incorrectly

assume that this is the flask itself.

There are also occasional movements from the Royal Navy dockyards at

Devonport and Rosyth of spent fuel rods from nuclear submarines. Unlike

the civil power station traffic that uses the standard FNA nuclear flask

wagons, the MoD employs two huge transporter trucks rather like transformer

wagons to carry the waste. These trains are classified under the Official

Secrets Act and always travel to Sellafield with at least one support

coach containing an armed escort

.

Amongst the other hazardous cargoes moved to Sellafield by DRS are bulk

chemicals used in the nuclear recycling process, namely nitric acid

(from Sandbach) and caustic soda (from Runcorn Folly Lane). There is

also a local trip working of low level nuclear waste from Sellafield

to British Nuclear Group’s Drigg repository. Following a major

restructuring of the UK’s nuclear industry, the Sellafield site

is now owned by the Nuclear Decommissioning Authority (see below), although

day to day operations are actually contracted back to British Nuclear

Group, a newly created subsidiary of BNFL.

In July 1999, DRS moved its headquarters from Sellafield

to the former BR Traction Maintenance Depot at Carlisle Kingmoor. Refurbished

at a cost of £1m, Kingmoor has provided the Company with a highly

strategic base alongside the West Coast Main Line from which to expand

beyond its core nuclear business. This process had actually begun a

couple of years earlier when DRS ran trials for both Tankfreight (a

logistics company interested in using rail to transport milk from Cumbrian

dairies to London) and Carlisle-based road haulier, Eddie Stobart. The

latter trial was supposed to have been conducted in secret, but as with

many of these things, word soon leaked out and a furious Stobart launched

a scathing attack on the railfreight industry, vowing never to use rail

again.

In early 2001, however, DRS won a contract with Scottish

logistics company, WH Malcolm, for a new Daventry-Grangemouth service.

This operation has grown from two trains a week to two a day including

a Daventry-Coatbridge flow and an Aberdeen service.

Additional business won during 2005 included a daily

Widnes-Purfleet Thames Terminal intermodal service for AHC (Warehousing)

Ltd., and a Network Rail weed-killing contract.

Considering its reputation as a niche operator, DRS

can boast a particularly interesting and varied motive power fleet,

which includes Classes 20, 33, 37 and 47. During its formative years,

the Company pursued a policy of buying (and then refurbishing) second-hand

locomotives from a variety of sources, but in January 2003, it signed

a deal with Porterbrook Leasing for ten new General Motors-built Class

66/4s. The first five machines, resplendent in a vibrant new DRS colour

scheme, arrived in the UK the following October and were immediately

put into service on the WH Malcolm traffic. This allowed the six ex-Hunslet

Barclay Class 20/9s (three of which worked to the Balkans in 1999 on

the Kosovo "Train for Life") to be withdrawn. Up until that

point, DRS had 21 Class 20s (including a number of ex-RFS Industries

examples used on the Channel Tunnel construction project) on its active

list, with a similar number in store pending possible refurbishment.

Many of these were in a particularly poor condition and in early 2005,

a small batch were sold to Harry Needle in exchange for several Class

37s. And, just as this article was in preparation, DRS announced that

it had sold its four Class 33s (always regarded as something of a specialist

fleet with no long term future) to Carnforth-based West Coast Railway

Company, again in exchange for two Class 37s. DRS has long favoured

this locomotive type and includes amongst its active fleet, nine of

the ex-BR European Passenger Services Class 37/6s. These machines were

heavily re-engineered during the early 1990s for use on Channel Tunnel

sleeper traffic but when the infamous Nightstar project was abandoned

in 1997, six of the twelve locos were put up for sale, and the fledgling

DRS quickly snapped them up. A further three were acquired from Eurostar

(UK) several years later.

During 2004/05, DRS trialled several Class 87 electric

locos with a view to introducing them on the Malcolm logistics traffic.

This was in direct response to an SRA strategy document which sought

to eliminate diesel traction from the two-track West Coast Main Line

north of Crewe after full introduction of the 125mph Virgin Pendolino

service. Whilst the 87s offered improved acceleration and better performance

(particularly on the tortuous route north of Preston), DRS ultimately

decided that the locos did not meet the Company’s operational

requirements, largely because the facilities at Grangemouth and Daventry

(and Kingmoor depot itself!) are not electrified.

On 1 April 2005, ownership of DRS together with many

of the UK’s ageing nuclear assets was transferred to the new Nuclear

Decommissioning Authority (NDA). As its name suggests, the NDA will

oversee the decommissioning and clean up of the UK’s nuclear legacy.

There are now only four first generation Magnox power stations still

in operation: Dungeness A, Sizewell A, Oldbury and Wylfa. The first

two are scheduled to cease operations in 2006, Oldbury in 2008 and Wylfa

(on Anglesey) in 2010. The Magnox reprocessing plant at Sellafield is

due to close by 2012. That does not, however, mean the end of nuclear

waste trains in the UK as there will still be flask traffic (although

much less of it) from the second generation Advanced Gas Cooled Reactors,

which should continue operating into the 2020s. And during 2006, the

Government will finally make a decision on the country’s long

term energy needs. With the UK's oil and gas reserves rapidly depleting,

an urgent need to reduce harmful CO2 emissions, and renewable energy

still in its infancy, the tide is once again turning in favour of nuclear

power. We should not really be surprised. Despite its relatively high

capital costs, nuclear energy is extremely cheap; in fact, one 6gm pellet

of MOX fuel can provide the same amount of energy as one tonne of coal.

DRS continues to follow the debate with interest but

the Company is now so firmly established in the railfreight market that

its long term future seems assured, regardless of UK energy policy.

|